Docks

A dispatch from July 2024

My three-year-old son is napping. The house is quiet, three ducks are floating by. An elm tree leans its face into the breeze the way a maned lion might, lazily, cooling off. On the corrugated roof before my second-story window, the debris of Tropical Storm Beryl—branches, twigs, clumps of leaves, pinecones—are as still as a painting. A cormorant flaps over the lake, an insect rattles. A jet ski trails its tail of spray.

What is it lake water does to me? Lake water lapping on wooden docks, lapping from the annals of my childhood. It’s a melancholy kind of longing—to be a boy again? To have lived a different life? To meet God? There was the dock at Uncle David’s where he would take us—me, my brothers, and our cousins—wakeboarding, skiing, tubing. He turned hard and the tube’s edge went airborne and we hung tight. There was the dock at Lake X an hour south of Orlando where we reeled in catfish and our grandfather cleaned and cooked them. From a dock in Colorado I kayaked with my brothers and later, the woman who became my wife. The look and sound of lake water lapping on docks sank into me, made permanent associations, made an appointment with me decades in the future, here in Houston, after Beryl.

What is the point of this appointment? A monarch butterfly twirls into and out of view. A wasp knocks into the windowpane and hurries away, embarrassed. The lake is alive with ripples. The shadow of a hawk or a great blue heron invades the still life, passing over the docks and the water. What color is this water? Brown beside the dock, but farther out a slate gray that you want to call blue. I want to lean my face into the breeze like the elm tree. An omnipotent God could have arranged each life as a continuous adventure, each scene building on the last like a well-written drama, but mostly it’s debris. If his ways are above our ways, they feel beneath us. All the ripples are moving right like a herd, like billions of souls on the way to Judgment. But the elm is leaning left.

There is so much I haven’t noticed. It took me hours to see the things in front of me, which my brain automatically tossed into a trash bin called Detritus. On the corrugated roof are sunlight and the swaying shadows of a giant oak. Another wasp knocks into the window. A red-bellied woodpecker alights on the oak, hops, flits, pecks, drops and swoops to the elm. I see its red cap through the leaves. A pair of cormorants flap and glide, flap and glide, most of life is flapping but I want to glide, gliding is the truest flight.

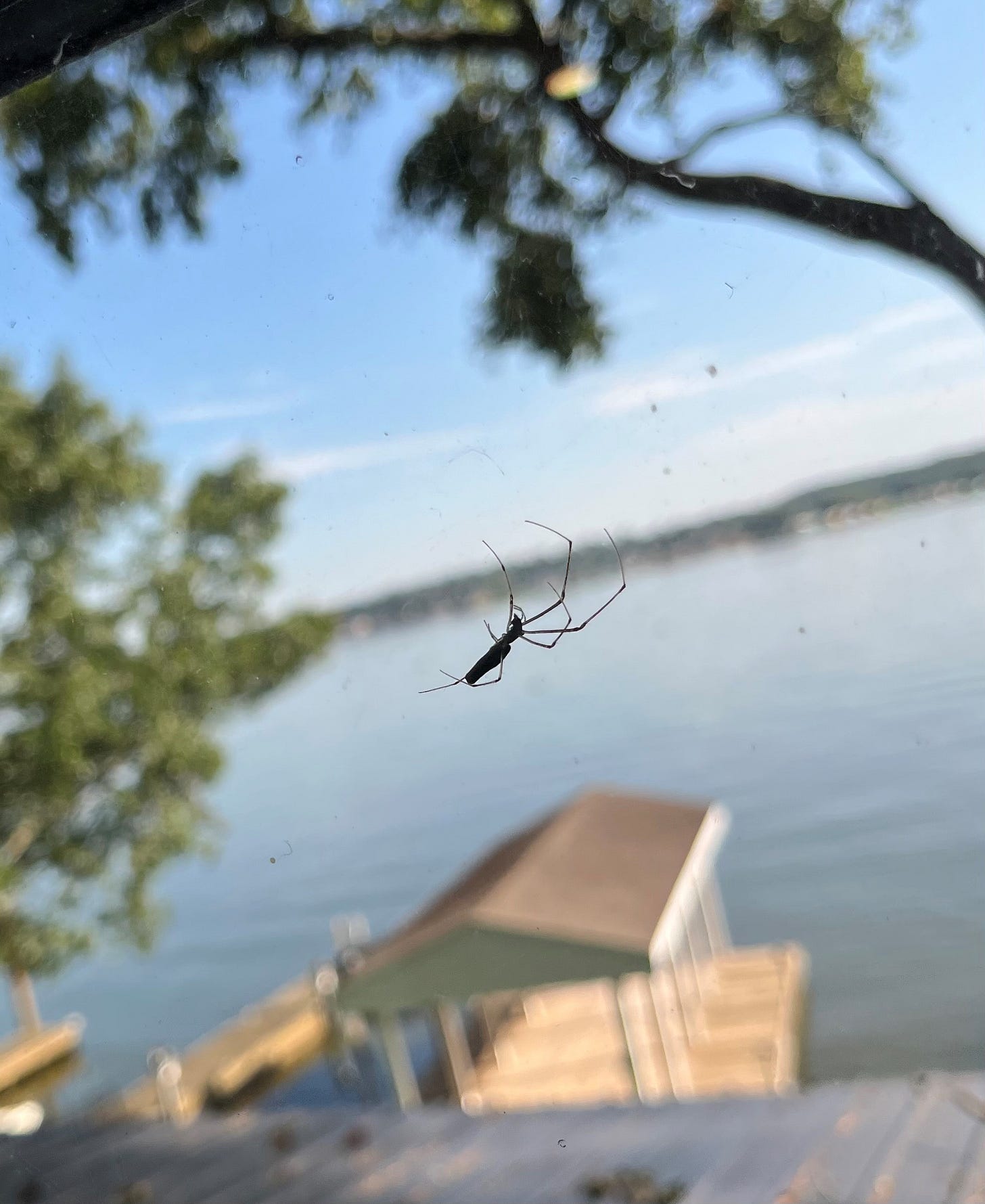

A squirrel has scaled the oak, which curls left with wabi-sabi nonchalance, a hulking wannabe bonsai, before sprouting branches and leaves. A spider struts and climbs invisible silk before the window. A dog barks, an airplane hums. I’m supposed to be working. Work feels more pointless than usual after a tropical storm, after two days without power, when the world was fine without me.

What is the mystery under these docks? They roll out into the water like bright articulate tongues. What do they say? Maybe God is more painter than dramatist. Maybe life is more hodgepodge than story. Still, one wants to connect the dots and string them up into a lovely wholeness.

If I sit up straight, the sash blocks the horizon so that the lake seems one with the sky. The illusion was more convincing in morning light. Now the sky is clean blue and the ruffled, granular water a different thing.

The house is waking up. I am being sent to attempt to fill the tank with gas.

I have filled the tank with gas. It came out slowly but it came. Waiting, I heard an older woman at the next pump chatting with an older man, apparently a friend or neighbor, who asked where her husband was.

“Cleaning up trees.”

“What?”

“Cleaning up trees. Cleaning up limbs and trees.”

“Oh! I had to do that with the last storm.”

“I called the county,” she said. “They’re supposed to send someone out to collect them.”

“Our government sucks anymore,” the man said. I thought he had in mind the shrinking of government by those who want less of it, but he added: “Thanks, Mr. Biden.”

The woman laughed. “‘It’s not me, it’s just my brain.’ D’you hear that one?”

“Someone needs to put a bullet in that brain.”

The woman giggled again. “I’m surprised Obama survived,” she said.

I wished to hear more, but my gas pump clicked and I was on my way.

The light on this corrugated roof has moved. I believe there are fewer pinecones. My still life won’t stay still. It keeps wanting to be a story.